One Cup, two countries

On how, in 2014, the Brazil that is synonymous with the most acclaimed football in the world will meet the Brazil that is penalized by poor infrastructure and a champion when it comes to corruption

The World Cup to be held from June 12 to July 13 next year will be the most difficult in history as far as Brazil is concerned. This prospect of a tough time ahead for a nation with a worldwide reputation as the “country of football” — the only team to win the trophy five times and take part in every championship since the tournament kicked off as a modest affair in Uruguay in 1930 with only four European teams participating – does not just refer to the sporting chances of manager Luiz Felipe Scolari´s team. Nobody would be foolish enough to underestimate Brazil, particularly playing on home ground, even in a highly competitive World Cup that will include all the teams that have already won it. This cautious approach stems more from off-field factors which Brazil will not have the luxury of being able to relegate to second place this time. Regardless of what happens and who wins the trophy, one thing is certain: Brazil will be facing Brazil in the World Cup. This will put the country that has been celebrated and acclaimed for playing the best football in the world up against the country that is penalized by poor infrastructure, hamstringed by a weak education system, permanently in the lower division in terms of social inequality and a champion when it comes to corruption. Neither of these two views is a lie but obviously they do not match when seen in the mirror.

This makes the 2014 Cup unique since Brazil runs the risk of losing even if it wins the trophy. For the first time, it will not be enough to win on the pitch. The competition will be much more challenging than it was in 1950 when the World Cup organized by Fifa was a parochial affair compared with the mega event it has become today. Brazil will need to win when it comes to airports, hotels, taxis and lines of people waiting at the stadiums and in terms of security — in short, in terms of organization. This game has already got underway and Brazil is lagging well behind as a result of projects that are running late, promises that will never get off the drawing board, budgets that have got out of hand and pitiful excuses like that of the sports minister, Aldo Rebelo, who said he had never seen a bride arrive at the church on time. If the Brazil that is good on the ball is the bride, the country that offered to host the Cup is the church itself. Despite the obstacles lying in the way and the scaffolding that might still be cluttering up the altar, everything will work out without any major problems, with a bit of luck. Even if this does happen, it does not mean the game is won. Brazil will have to show the watching world that the “country of football” label is not just an empty slogan that a large part of the population, gathered outside the church with rocks rather than rice in their hands, looks at with anger and disdain as if the whole event was nothing more than publicity stunt aimed at fooling the masses.

After all, is Brazilian football similar to that worn-out Marxist cliché the “opium of the people” or is it the most refined expression of the national culture? Both, obviously. If we get rid of one, the country of 11-year-old Deyvid Arnaldo da Silva, born and raised in Itaquera, a district in the eastern zone of São Paulo where a race against the clock is underway to build the stadium where Brazil will face Croatia in the opening game, will be incomplete. Deyvid is the youngest child and only boy among the four children of Josinaldo, an asphalt worker from Pernambuco state, and Rosilda, a cleaner. His ambition is to revive his father´s frustrated dreams and become a professional footballer. To do so, this small, skinny kid plays on a rough makeshift pitch in Rua Professor Leonidio Alegreti, next to Itaquerão, the unfinished stadium where two workers were killed in November when a crane fell and set the timetable back. Deyvid is poor — his uncle pays his monthly football school fees — but he dreams on a large scale. Even though he has no money to buy a ticket, he thinks he can “find a way” to get into the stadium and see his idols close up. This is only the start. “I want to be like Messi, the best in the world,” he says. There is little chance of this coming about but only someone who does not know Brazil would regard it as completely impossible.

Like it or not, this is the complicated equation that will dominate 2014. To reject any of these two images of Brazil as a lie or irrelevant – that which the passion for sport exalts or the civic awareness reveals – would be to waste a historic opportunity. The big picture was not reflected in press comments by Nizan Guanaes of the Africa advertising agency when the Cup groups were selected in the first week of December. “Screw the state of the airport, the fact that the taxi driver can´t speak English, screw everything. All that matters now is the passion for football and, as we all know, love is blind.” As if Brazil´s airports needed any further encouragement to screw things up! For the same reason, the English writer and journalist John Carlin seemed naïve when he said he could not understand the strength of Brazil´s social dissatisfaction in a recent article he wrote for VEJA. “How could this happen?” he asked in surprise and claimed that “there can be no better place to celebrate the biggest football party in the world”. The former French star Michel Platini, president of Uefa, the body that runs European football, joined the chorus opposing any demonstrations against the Cup. In an interview with the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, he made a threat that no-one believed, “If I have to watch the games surrounded by security guards and soldiers, I will not come to Brazil”.

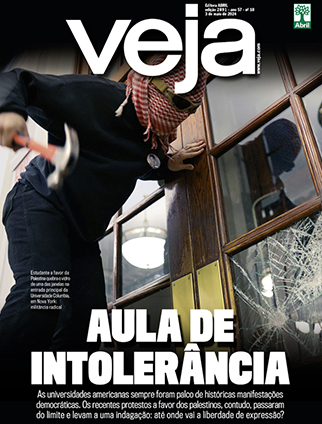

“WE ARE UNBEATABLE” – Dilma Rousseff said in her speech at the inauguration of the Arena Fonte Nova stadium in Salvador (pictured with state governor Jaques Wagner): “We are a country known for being unbeatable on the pitch but we are also showing that we are unbeatable off the pitch.” Only a few meters away, a giant bilingual direction board outside the stadium had translated the Portuguese word “saída” which means “exit” as “entrace”. Not only did this give the opposite meaning but also misspelled the English word (Roberto Stuckert Filho/PR/AFP – Jornal A Tarde)

“WE ARE UNBEATABLE” – Dilma Rousseff said in her speech at the inauguration of the Arena Fonte Nova stadium in Salvador (pictured with state governor Jaques Wagner): “We are a country known for being unbeatable on the pitch but we are also showing that we are unbeatable off the pitch.” Only a few meters away, a giant bilingual direction board outside the stadium had translated the Portuguese word “saída” which means “exit” as “entrace”. Not only did this give the opposite meaning but also misspelled the English word (Roberto Stuckert Filho/PR/AFP – Jornal A Tarde)

Of course Platini will come and, if necessary, he can expect a security scheme that will ensure he and all the participants have the protection the authorities failed to give the victims of the shocking outbreak of violence between supporters of Atlético Paranaense and Vasco da Gama in Joinville on December 8 in the final game of the Brazilian Championship. Trying to cover up the facts with words is bad politics and made President Dilma Rousseff the butt of jokes when she jumped on the nationalist bandwagon in a speech at the inauguration of the Arena Fonte Nova stadium in Salvador in April of last year. She claimed that “we are a country known for being unbeatable on the pitch but we are also showing that we are unbeatable off the pitch.” Only a few meters away, a giant bilingual direction outside the stadium board had translated the Portuguese word “saída” which means “exit” as “entrace”. Not only did this give the opposite meaning but also misspelled the English word. As Carlin asked, “How could this happen?”

The chance of reconciling the Brazil of the dream and the real Brazil begins by recognizing that while the “country of football” is a myth, it is far from being a lie. In order to support the deluded political argument that surrounds many pre-Cup conversations — that the world´s most popular sport is nothing more than a fraud controlled by an imperial outfit, Fifa, to allow large companies to make big profits at the expense of the naïve fan — we need to get rid of the idea of beautiful Brazilian football, an epic that coincides perfectly with the political and social development of the country in the 20th century. Among the stories of the creation of a national identity, the one that revolves around the ball and fills the dreams of boys like Deyvid da Silva is the most successful as far as the domestic and international public is concerned. We can highlight the following characters in the gallery of heroes of this saga in order of appearance (each with his nickname as is the case with mythological creatures): Arthur Friedenreich, el Tigre; Leônidas da Silva, the Black Diamond; Pelé, the King; Ronaldo, the Phenomenon; and the novice, Neymar, the great Brazilian hope in 2014, still waiting for a definitive nickname to replace the disparaging Skinny which manager Vanderlei Luxemburgo tried to apply. All were or are black or of mixed race. This is a story in which poor players took over and sculpted from the bare stone of a European game a face full of surprises and sinuous lines that the world revered as the “Brazilian school. The Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini gave an example in an article he wrote in 1971 on the impact of Brazil being the world champions for the third time when he referred to the Brazilians´ “poetic” football as opposed to the Europeans´ “prosaic” football.

There is no doubt that football lovers throughout the world often turn the golden era of the Brazilian team into a myth as though those star players from the past were supernatural beings who never made a bad pass. Compared with this unattainable dream, they are overcritical of today´s players. It is also obvious that this myth was created historically in victorious times that led unsuspecting critics, like the English historian Eric Hobsbawm, to promote a mere game to the category of artistic expression for the first time. Yes, we are talking about Brazil´s main artistic contribution to the world, according to the world itself, with its popular music making an honorable appearance as runner-up. All this belongs to the sphere of legend but it is worth recalling the lesson of Joseph Campbell, the great American writer on myths, who said that myths show traces of the spiritual potential of human life. When a cultural expression gets so rooted in the collective consciousness of a people, as has occurred with football in Brazil, it needs to be treated with respect. The signs that show who we really are in that metaphorical mirror the World Cup will put in front of us may very well become apparent to everybody in the most familiar features of our style: improvising, refusing to plan ahead and opting for the last minute solution. These are the same features that turn a football player into a star and an administrator into a failure. At the end of the day, Brazil is only one country.

Renata Lucchesi contributed to this article

* Sérgio Rodrigues, writer and journalist, contributor to the VEJA site and author of the novel O Drible

An epic of assertion

The great names of Brazil´s footballing history follow the classic trajectory of the myth: that of a common man submitted to a series of torments until by his own force he ends up as a hero

THE REDEEMER OF THE MARACANAZO DEFEAT – Pelé, the greatest of all the heroes, would only enter the scene in the role of redeemer after Brazil´s defeat in the World Cup final of 1950 (known as the Maracanazo) which the anthropologist Roberto DaMatta called “perhaps the greatest tragedy in Brazil´s contemporary history”. The consecration of Pelé as the king of football in 1958 left his successors — even those who were brilliantly gifted, such as Ronaldo and Neymar — with the burden of being compared with giants. It was though the time of myths had ended and it was now time for mere mortals to do the best they could

THE REDEEMER OF THE MARACANAZO DEFEAT – Pelé, the greatest of all the heroes, would only enter the scene in the role of redeemer after Brazil´s defeat in the World Cup final of 1950 (known as the Maracanazo) which the anthropologist Roberto DaMatta called “perhaps the greatest tragedy in Brazil´s contemporary history”. The consecration of Pelé as the king of football in 1958 left his successors — even those who were brilliantly gifted, such as Ronaldo and Neymar — with the burden of being compared with giants. It was though the time of myths had ended and it was now time for mere mortals to do the best they could

The fullest version of the epic of assertion of Brazilian football was written in 1947 by the sports journalist Mario Filho who would give his name years later to the Maracanã stadium. His book O Negro no Futebol Brasileiro (The Black in Brazilian Football) was reissued with substantial additions in 1964 to take in the Pelé era. It added an aspect of cultural and racial struggle to the journalistic coverage of the growing popularity of a game that was originally elitist. The book pointed out curious similarities with other examples of sport being appropriated by groups that were political outcasts and even ended up in musical metaphors.

The style Brazil´s black and mixed race players imposed on a hard physical game that originated in England appeared to sociologist Gilberto Freyre, who admired Mario, like the capoeira martial art that brings together dance, music and movement and the popular samba music. In his book Football in the Sun and Shade, the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano hailed the football played in Uruguay and Argentina. He said that “the touch was born in the feet of the first creoles: they touched the ball as though it was a guitar, a source of music”. Meanwhile, the American writer Nelson George, author of Elevating the Game, identified the origin of the improvisation and rhythmic variations which American blacks used to revolutionize basketball in the energetic jazz of the 1920s and 30s.

This is not just coincidence. What is seen in all these cases is not so much a documented history as a parabola of cultural assertion that can be reduced to the classic scene from the myth: a common man (in this case, a group) is submitted to a series of torments, including coming close to death (the overwhelming trauma of Brazil losing the World Cup final in 1950) until he ends up as a hero (winning the World Cup). It is also no coincidence that the first edition of Mario Filho´s book appeared at the time of the New State. Its nationalism, tinged with racial optimism based on theories of eugenics, hailed miscegenation as Brazilian civilization´s most original contribution.

The first chapter of this saga corresponds to the Old Republic. The end of slavery was still fresh and that highly regulated game created by white English lords in the 19th century and played by young members of the upper classes in their clubs was, therefore, looked down on by writers who identified with the people. These included Graciliano Ramos from Alagoas state who wrote in 1921, “We have plenty of sports. Why should we get involved with foreign things? You can be sure that football will not take off.”

However, it already had taken off even by that time. Arthur Friedenreich, a light-skinned mulatto with green eyes who was the son of a German and a black Brazilian woman, had established himself two years previously as the first great idol of Brazilian football by scoring the winning goal in the South American championship final against Uruguay. This was the Brazilian´s team´s first important victory. The black man in Brazilian football makes Friedenreich the first hero in this story but the extent of the difficulties to be overcome required more than the efforts a mulatto disguised as a white man.

The second chapter coincided with the Revolution of 1930 when the hypocritical amateurism of the time gave way to professionalism and the lead was taken by someone who was indisputably black – Leônidas da Silva from Rio de Janeiro. He won the reputation of having invented the bicycle kick although this has been disputed. He was the striker in the 1938 Cup and the main player in the Brazilian team which came third in that competition. However, Leônidas´s international career was thwarted by the break in international games from 1942 to 1946 brought about by the Second World War and he became a kind of precursor of Pelé.

Pelé, the greatest of all the heroes, would only enter the scene in the role of redeemer after Brazil´s defeat in the World Cup final of 1950 (known as the Maracanazo) which the anthropologist Roberto DaMatta called “perhaps the greatest tragedy in Brazil´s contemporary history”. The consecration of Pelé as the king of football, which ends Mario Filho´s book on a nationalist note, left his successors — even those who were brilliantly gifted, such as Ronaldo and Neymar — with the burden of being compared with giants. It was though the time of myths had ended and it was now time for mere mortals to do the best they could. However, the truth is that the beautiful epic of Brazilian football is still being written and a new chapter will begin in June.

SEGUIR

SEGUIR

SEGUINDO

SEGUINDO

Galvão Bueno tem contas penhoradas por dívida milionária de vinícola

Galvão Bueno tem contas penhoradas por dívida milionária de vinícola Shopping se manifesta sobre ‘calote’ de Taís Araújo

Shopping se manifesta sobre ‘calote’ de Taís Araújo Mais um dia na vida de Elon Musk: ações da Tesla caem, carros encalham

Mais um dia na vida de Elon Musk: ações da Tesla caem, carros encalham A milionária conta dos carros blindados de Eduardo Paes no Rio

A milionária conta dos carros blindados de Eduardo Paes no Rio Interpol atende Argentina e emite alerta de prisão contra ministro do Irã

Interpol atende Argentina e emite alerta de prisão contra ministro do Irã